Are you a fashion history lover looking for something to see and do this holiday season? If yes, you must visit the Brandywine area to see the Ann Lowe: African-American Couturier exhibition at Winterthur.

It is sad that forty-two years after Ann Lowe’s death, the hidden figure’s talent receives this significant recognition. The Ann Lowe exhibit at Winterthur runs until January 7, 2024. Admission fees: general admission is $29.00; I take advantage of senior discounts: $27.

It is sad that forty-two years after Ann Lowe’s death, the hidden figure’s talent receives this significant recognition. The Ann Lowe exhibit at Winterthur runs until January 7, 2024. Admission fees: general admission is $29.00; I take advantage of senior discounts: $27.

It’s all in the family at Winterthur, another du Pont estate. Pierre Samuel du Pont created Longwood in 1906. His cousin, Henry Francis du Pont, created Winterthur as a museum of American decorative arts in 1951.

On my first trip to the National Museum of African-American History and Culture in 2016, I discovered the remarkable, influential Ann Lowe. I felt compelled to learn more about Ms. Lowe with my post in 2019.

T

T

The 2020 racial reckoning with George Floyd’s death uncovered many unsettling everyday situations with Black people. A few examples are the lack of respect or acknowledgment of our contributions to society. It was no different for little-known groundbreaking designer Ann Lowe during her reign. Even Jackie Kennedy only acknowledged Ann Lowe as the “colored seamstress” who made her gown.

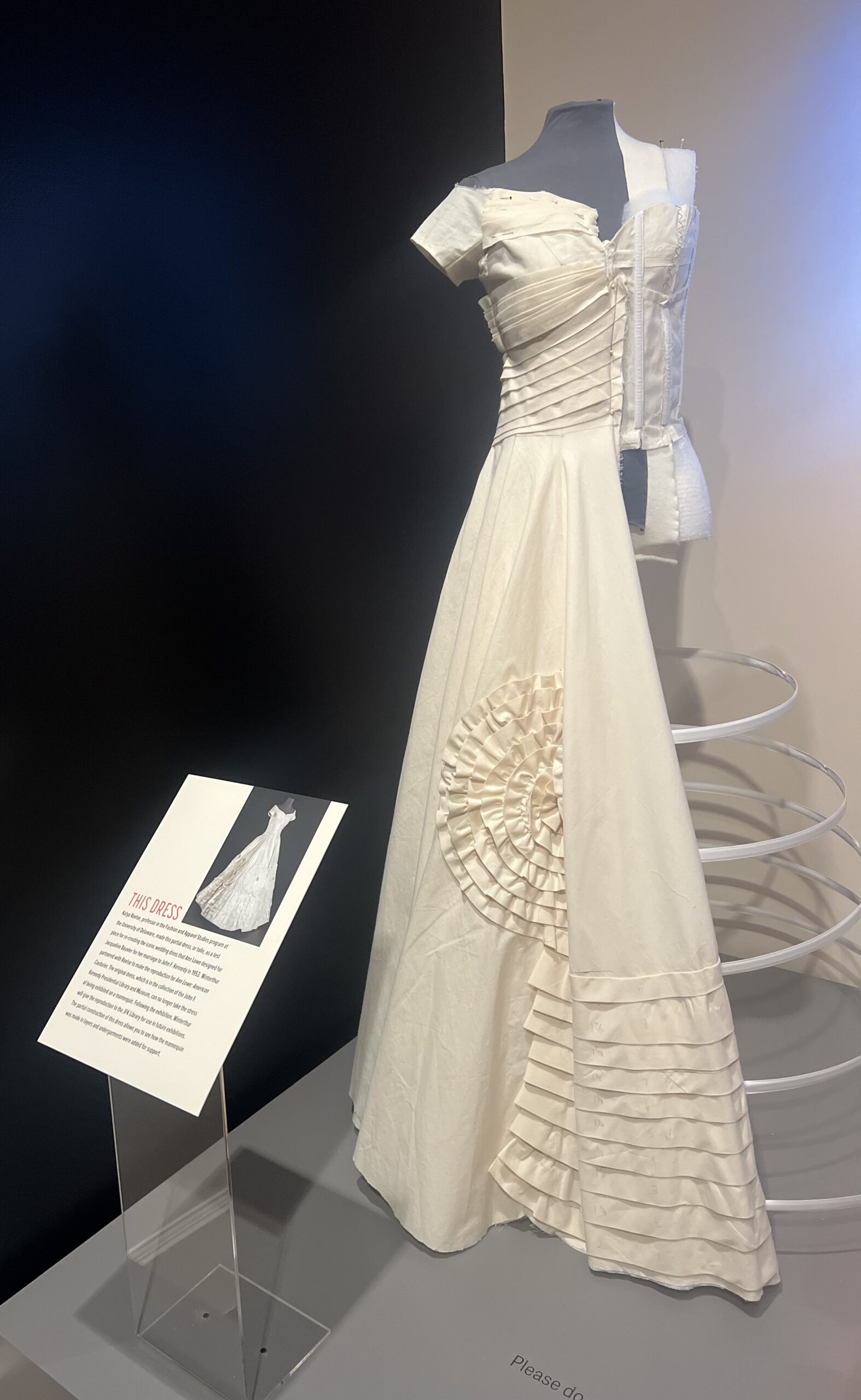

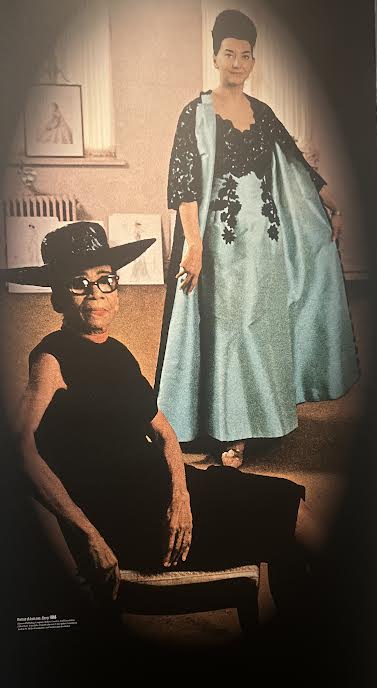

Ann Lowe (1889 – 1981), from Clayton, Alabama, designed and created her most famous dress for Jacqueline Bouvier for her 1953 wedding to John F. Kennedy.

Katya Roelse, an instructor in the Fashion and Apparel Studies program at the University of Delaware, made this partial reproduction of Jacqueline Kennedy’s first wedding dress. It took Ms. Roelse six months to complete the partial recreation. The original 1953 dress resides in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum collection in Boston, Massachusetts, and is too fragile to travel.

I learned that Jackie Kennedy’s father-in-law insisted she wear an American brand to communicate diplomacy. During this time, Ann Lowe was already a sought-after dressmaker. To Who? The elite East Coast families like the Rockefellers, Du Ponts, and Roosevelts for bespoke wedding and debutante gowns.

Noted for her exquisite attention to detail with pristine pleating on a gown’s bodice, intricate scallop pin tucks, and complex rosette embellishments, all done by hand, are trademarks of Ann Lowe.

Noted for her exquisite attention to detail with pristine pleating on a gown’s bodice, intricate scallop pin tucks, and complex rosette embellishments, all done by hand, are trademarks of Ann Lowe.

Lowe learned the craft of 19th-century-style custom dressmaking from her mother and formerly enslaved grandmother. Both ladies ran a business together during Reconstruction in the Jim Crow era. When Ann’s mother died, she took over the business after dropping out of school at 14.

Fast forward to two failed marriages, a son and an adopted daughter. Anne moved to New York City in 1917. She enrolled at S.T. Taylor Design School. The school didn’t know Ann was Black until she showed up on the first day. To appease the majority of White students, Ann sat by herself to learn where she excelled and graduated in half the time required; after graduating in 1919, Ms. Lowe moved to Tampa, Florida. The following year, she opened her first dress salon, “Ann Cohen,” catering to generations of famous families, especially debutantes.

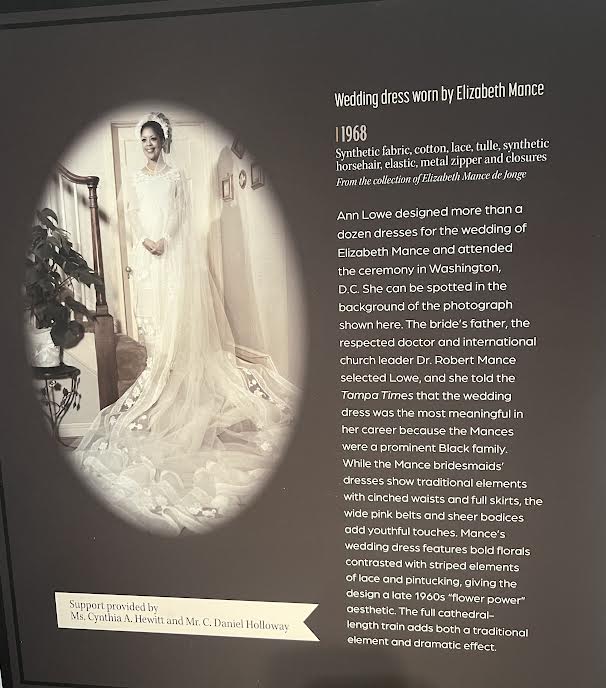

Lowe also created dresses for clients such as pianist Elizabeth Mance from a prominent Black family.

According to online sources, in 1961, Ms. Lowe received the Couturier of the Year Award. In her later life, Lowe struggled with both health and finances. In 1962, she lost her salon in NYC after failing to pay taxes. Then, unfortunately, the same year, Ann underwent eye surgery to remove her right eye damaged by glaucoma. In 1968, she opened a new store, Ann Lowe Originals, on Madison Avenue. She retired in 1972 and died at her daughter’s Queens home on February 25, 1981, at the age of 82, after an extended illness.

According to online sources, in 1961, Ms. Lowe received the Couturier of the Year Award. In her later life, Lowe struggled with both health and finances. In 1962, she lost her salon in NYC after failing to pay taxes. Then, unfortunately, the same year, Ann underwent eye surgery to remove her right eye damaged by glaucoma. In 1968, she opened a new store, Ann Lowe Originals, on Madison Avenue. She retired in 1972 and died at her daughter’s Queens home on February 25, 1981, at the age of 82, after an extended illness.

The idea for an exhibit about Lowe began with Winterthur textile historian Margaret Powell. Her 2012 Master’s Thesis was the first comprehensive study of Lowe. Powell’s research became the foundation of the show. Powell left Winterthur to curate at the Carnegie Museums in Pittsburgh, unfortunately dying in 2019.

The idea for an exhibit about Lowe began with Winterthur textile historian Margaret Powell. Her 2012 Master’s Thesis was the first comprehensive study of Lowe. Powell’s research became the foundation of the show. Powell left Winterthur to curate at the Carnegie Museums in Pittsburgh, unfortunately dying in 2019.

A posthumous thank you to the late Margaret Powell for allowing Ann Lowe’s legacy to have a place in African American history and no longer be a hidden figure. And a chef’s kiss to Winterthur for forging ahead to bring Ms. Powell’s passion for Ann Lowe to life.

.

Congratulations to the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) associate curator and the exhibition’s guest curator, Elizabeth Way. And her team for highlighting Ann Lowe’s 40 intricately constructed custom-made gowns on display. Before the two-year project started, Way put out an APB requesting uncatalogued Ann Lowe gowns. In response to the APB, many of the gowns are from private collections on loan for this exhibition. And a few from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute and the Fashion Institute of Technology collections.

Dressmaking was some of the highest-paid, most respectable work for women, Black or White, in the 19th century which they could according to an online source, Lowe was proud of her connections to high society, telling Ebony: “I do not cater to Mary and Sue I sew for families of the Social Register.” Anyone watching the Gilded Age, if yes, you can relate.

Lowe maintained a staff 35 at her best, made nearly 10,000 dresses in one year, and grossed approximately $300,000 annually. The exhibition leaves one appreciating Ann’s astounding craftsmanship, exploring her life, and feeling you know Ann Lowe’s accomplishments as an African-American couturer.

As always, thank you for visiting The Age of Grace. Merry Christmas to you and your family.